By Seminar Information Systems (WS19/20) | February 6, 2020

Big Peer Review Challenge

Asena Ciloglu & Melike Merdan

Abstract

This blog post studies the first public dataset of scientific peer reviews available for research purposes PeerRead applying state-of-the-art NLP models ELMo and ULMFit to a text classification task [1]. It aims to examine the importance of the peer reviews on paper’s acceptance or rejection decision in well-known conferences of computational linguistics, AI and NLP.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Descriptive Analytics

- Application

- Empirical Results & Conclusion

- Reference List

1. Introduction

1.1. Peer Review Process

Figure 1: Peer Reviewing Process – Image Source: Flickr AJ Cann, CC BY SA

Peer review is a formal method of scientific evaluation that appeared in the first scientific journals more than 300 years ago. The philosopher Henry Oldenburg (1618-1677) is accepted as the pioneer of the modern peer review process due to his initiation of the process in the journal of The Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society [17]. The peer review framework is designed to determine the validity and quality of scientific papers for publication. In this way, it is aimed to maintain certain quality standards and credibility for a journal.

When a manuscript is submitted to a scientific journal, it goes through various steps before it is published in the journal. Firstly, the article goes to the editor for a preliminary check if it satisfies the journal’s requirements. The manuscripts that pass the editor’s evaluation are then sent out for peer review. During the peer review process, the paper is assessed by multiple competent researchers in the field. The reviewers evaluate the scholar work in several aspects such as appropriateness, clarity, substance, impact or originality and provide their evaluation on whether they would recommend the paper to be published or not. Consequently, these peer reviews go through the editor’s assessment and the decision on the manuscript’s acceptance or rejection is made. In some cases, the manuscript could be revised and resubmitted again for a final decision. A rejection does not necessarily mean the poor quality of the paper but it rather indicates the paper is not on the line with the journal-specific requirements.

Peer reviewing process is generally not paid since they are considered a valuable contribution to science and research and hence the process voluntary and self-regulatory. In this regard, their robustness and efficacy have been discussed by the experts and there are several approaches suggested to these processes. The traditional way is the single-blind reviewing process where the names of the reviewers are not shared with the author, and therefore any possible negative interaction between the author and the reviewer is avoided. However, the reviewers are able to observe the author’s name and this could potentially lead to a bias towards the author. To tackle the problem, double-blind reviews are introduced where neither the reviewer nor the author observes each other’s name. The anonymity is expected to prevent biases based on the name, gender, or reputation and provide a more reliable environment for scientific work. Despite this, there exists also other methods such as a third-blind review or open review yet the aforementioned two are the most common current approaches.

1.2. Motivation

Though the double-blind review process is introduced to limit possible biases, it has been discussed whether reviews could still identify the authors through their writing style or methodology and whether the process might be totally anonymized. This ongoing criticism about the integrity, consistency and general quality of peer review motivated us to elaborate more on the data available and determine if the data gives us any hint about the questions addressed to peer reviews since peer reviews are still believed to be the best form of scientific evaluation and used by the majority of scientists including prestigious venues.

NIPS Experiment

In 2014 the organization committee of the NIPS Conference, one of the largest conferences in AI, conducted a thought-provoking experiment where they tasked two committees to review the same 10% of the conference submissions to assess the consistency of the peer review process [10]. The committees were assigned a certain acceptance rate of 22.5% but not told that the submissions are concurrently revised by another committee. In the end, the organizers observed that the committees disagreed on more than a quarter of the papers. In other words, approximately 57% of the total list of accepted papers by both committees are accepted by one of the committees and rejected by the other one given a set acceptance rate. This result addressed once again the robustness of the peer review process and questioned the consistency of the reviewers. In our study, we examine numerous articles submitted to reputable scientific conferences in the areas of computational linguistics, natural language processing and deep learning including the NIPS Conference, and their respective peer reviews. We aim to evaluate the consistency and effectiveness of the reviews on acceptance decisions of the submitted manuscripts by applying multiple text classification tasks with deep learning.

2. Descriptive Analytics

2.1. A Dataset of Peer Reviews

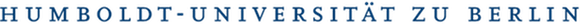

Our reference dataset is from the paper called A Dataset of Peer Reviews (PeerRead) [1]. The main purpose of this paper was to illustrate the extracted output of the PeerRead dataset and take us through the validation process of data extraction. They gathered 14.7K paper drafts and the corresponding accept/reject decisions in top-tier venues including Association of Computational Linguistics (ACL), Conference on Computational Natural Language Learning (CoNLL), International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS); 10.7K textual peer reviews written by experts for a subset of the papers. The four conferences usually serve for similar topics in academia such as machine learning, deep learning, computational linguistics, and natural language learning. In addition to that, they made use of the information on arXiv.com where they could only benefit from the paper itself. For consistency, only the first arXiv version of each paper (accepted or rejected) in the dataset is included and considered accepted if it is accepted in any of the valid scientific venues. The dataset source can be found here.

Their analysis is twofold: firstly they analyzed acceptance classification based on paper drafts; secondly, they predicted the aspect scores based on the reviews. In the first analysis, they used models such as Support Vector Machine, Logistic Regression, and Decision Trees while they did not prefer to use a machine learning algorithm as they evaluated them too hard to interpret in this task [1]. After each review had been held, the reviewer was asked to give aspect scores along with the review. The aspect scores are impact, substance, appropriateness, comparison, soundness, originality, and clarity. In order to predict aspect scores, they used machine learning algorithms such as CNN, RNN and Deep Averaging Networks (DAN).

2.1.1. Approach and Data Extraction

Through our analysis, we followed the PeerRead paper while constructing our dataset. Data collection varies across sections because each might have different license agreements. ACL and ConLL, ICLR and arXiv datasets were publicly available in JSON formats. For ConLL, we manually added the acceptance/rejection information. On the other hand, NIPS data had to be crawled due to license issues, however, it is also publicly available to do so.

Figure 2: Our Dataset

Figure 2: Our Dataset

It is important to note that, for ACL and ConLL datasets, we are only able to reach the opt-in reviews, where both the writer and the reviewer agree to share the reviews and the paper draft. This might cause a positive bias where papers with ‘good’ reviews might tend to reveal themselves than the rejected papers. Additionally, for NIPS, we are only able to reach the accepted papers since they only publicize the accepted papers’ information on their website.

2.2. Google Scholarly

Google Scholar is a web search engine that is freely available where anyone can reach the full text or metadata of scholarly literature across an array of publishing formats and disciplines [2]. To crawl information from Google Scholar, one can utilize a package available called ‘scholarly’. ‘Scholarly’ is a module that allows you to retrieve author and publication information from Google Scholar in a friendly, Pythonic way [3].

In our dataset, we first eliminated the papers without the authors publicly available, then extracted each author’s following information. As Google Scholar prints output similar to a dictionary, we first printed this output on a JSON file. Later on our analysis, we used the author’s affiliation with an institution, to see its predictive power on our task.

2.3. Data Cleaning

When performing Natural Language Processing tasks, data cleaning has a crucial role [4]. After cleaning the text from potential noise, one can conduct a powerful analysis.

Our cleaning consists of four main tasks: clearing from any punctuation, lower case all text, remove stopwords and stemming. Performing a ready-set stopword might cause loss of information, for example in our text analysis, we wouldn’t like to lose the word ‘not’ when working on a text classification task. Therefore, we first performed regular expressions cleaning, then removed the stop words that we agreed on.

Cleaning words with stemming is highly debatable. After performing stemming, we reach the roots of a given word. This enables us to end up with core words, with less unnecessary variations at the cost of losing some valuable information. Since the papers and reviews are already too long to work with, we decided to perform stemming as a part of our cleaning process.

2.4. Data & Insights

Checking our data for most common words, we do not observe much difference when checking for abstract or for reviews. From the below word cloud, one can easily see that ‘learn’, ‘model’ and ‘use’ have been the most common words for reviews. Furthermore, we performed a TF-IDF analysis to examine the weights of each word on acceptance or rejection. However, we did not see a notable difference in common words between accepted and rejected papers.

Fortunately, NIPS allowed us to reach 30 years of old author information for published papers. The below graph shows that most of the papers published on NIPS conference were written by more than one author, so through collaboration.

3. Application

3.1. Our Approach

3.1.1. Content-based Classification

Our first approach is a text classification analysis in deep learning based on the content of submitted papers. We aim to examine how much impact the content of a paper has on paper’s classification of acceptance or rejection. Our curiosity is driven by the question if there are some dominant topics or keywords with a higher probability to get accepted for publication. Furthermore, we would like to see how effective paper’s content in general on the classification. On that account, we would like to choose an approach where we provide a substantial and informative part of a paper while we keep being frugal to avoid computational heaviness. Thus, we used the abstract part of each paper since abstract is a summary of the study ascertaining the paper’s purpose, subject matter and sometimes briefly its methodology as well.

To obtain more reliable results, we used our entire dataset available for this analysis since we don’t have any paper without an abstract in our dataset. To be more precise, the dataset consists of papers submitted papers of ACL 2017, CoNLL 2016, ICLR 2017, NIPS 2014-2016, and arXiv 2007-2017 submissions. For the analysis, we used transfer learning methods ELMo and ULMFit and compared the results with a benchmark of Lasso Regression.

3.1.2. Review-based Classification

Our second approach is galvanized by our main motivation for peer reviews. By analyzing the body of peer reviews we would like to inspect their role on the final classification decision. A text classification task with deep learning methods, we believe, demonstrates how powerful and capable the reviews for acceptance or rejection. We expect that the reviews must be noticeably successful at predicting paper’s classification as long as they are relevant and consistent with the paper itself.

In this part of our analysis, we could use a small portion of our dataset since we were only given reviews from the four conferences but the arXiv submissions. To keep our dataset for the analysis balanced to some extent, we used the reviews from ACL 2017, ConLL 2016, ICLR 2017 that represent the whole dataset we have for these conferences but only the year of 2016 for the NIPS conference. The underlying reason is that the NIPS conference solely makes the accepted articles publicly available. For this task, we used again transfer learning methods ELMo and ULMFit and Lasso Regression for benchmark comparison.

3.1.3. Analysis with Auxiliary Data

Our last approach is based on the auxiliary data about authors’ institutions we scraped from Google Scholar archive. We intend to observe whether there is a positive bias towards authors from recognized institutions or negative bias towards authors from various other less known institutions. Although our dataset with an exception of ICLR 2017 consists of double-blind reviews as aforementioned above, it is not entirely impossible to identify authors by their writing style or methodology and create a bias accordingly. The dataset we obtained from ACL and ConLL conferences are the submissions that were opted-in to be published for academic research, and thus they did not contain any information about the authors. Therefore, we removed this part from our dataset and solely used the authors from ICLR 2017, NIPS 2014-2016, and arXiv 2007-2017 submissions. Even though we used the whole list of author names from these submissions, we ended up using approximately 50% of the dataset because some authors were not listed on Google Scholar and some of them have their names written differently and they did not match with the submissions in the end.

In this analysis, we used authors’ affiliation as text input to the model since one paper is commonly written by more than one author instead of factoring various affiliation categories from several authors writing one paper. Hence, we would like to use the SVM model that accounts for the frequencies of the terms via the TF-IDF method. We performed the SVM model to predict the article classification based on the only review, only institution, and both review and institution to observe the author’s affiliation’s impact on the acceptance or rejection decision.

3.2. Transfer Learning and Recent Applications

We sometimes have a task to solve in one domain of interest while we only have big enough data in another domain of interest where the latter data is much bigger and available to solve a classification task. Under these circumstances, transfer learning helps us to use the sufficiently big data to train our language model and benefit the information to solve the task of interest [6].

Deep learning enables us to learn non-linear relationships directly from data using neural network architectures. Deep learning has achieved impressive success in the field of computer vision by hitting the mark in image classification [7]. Inspired by ImageNet models on computer vision, transfer learning in Natural Language Processing has brought the field a long way [5]. In a text classification model, it firstly builds a language model to gain knowledge of the language distribution and then continues training the model on the specific classification task. When the language model is trained, it creates word vectors that hold the information about the input that can be applied to different tasks later. As word vectors as NLP’s core representation have gained importance during the past few years, a new line of state of the art models has emerged in this fields such as ELMo, ULMFit and Open AI Transformer [5].

3.3. Embedding for Language Models (ELMo)

The idea of applying transfer learning to NLP models influenced many data scientists in the year of 2018. From the very beginning until the end of the year, new NLP models using transfer learning appeared following one another. Embeddings from Language Models (ELMo) model emerged at the beginning of this flow and was introduced in February 2018 by the researchers of the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence (AllenNLP).

Its approach is basically training a language model on a large corpus, extracting features and using these pre-trained representations in a randomly initialized downstream models. It has 4 pre-trained models with a different number of parameters, highway layers, LSTM size, and output size: small, medium, original and original (5.5B). All models except for the 5.5B model were trained on the 1 Billion Word Benchmark, approximately 800M tokens of news crawl data from WMT 2011. The ELMo 5.5B model was trained on a dataset of 5.5B tokens consisting of Wikipedia (1.9B) and all of the monolingual news crawl data from WMT 2008-2012 (3.6B) [16].

3.3.1 Methodology

Unlike the commonly used word embeddings GLoVe and word2vec, ELMo word representations are deep contextualized and functions of the entire input sentence allowing to model the characteristics of word use (e.g., syntax and semantics) and how these uses change across different linguistic contexts (i.e., model polysemy). The word vectors are computed on top of a two-layer bidirectional language model (biLM) with character convolutions as a linear function of the internal network states that is pre-trained on a large text corpus. The model setup enables semi-supervised learning that can be incorporated into a wide range of NLP applications such as sentiment analysis and textual entailment [16].

3.3.1.1. Deep Contextualized Word Representations

ELMo has its power from its unique word representations that are character-based, contextual, and deep. These deep contextualized word representations account for the entire context in which it is used compared to the existing word embeddings GLoVe and word2vec that use set word representations regardless of the context. In other words, the word “stick” would have different representations when used in the following two sentences: “Let’s stick to the original plan!” and “I cannot find my USB stick anywhere!”. Even though the word “stick” is exactly the same, its contextual meaning varies across the sentences and thus its ELMo representations change accordingly as well. If we use the traditional word embeddings like GLoVe or word2vec, the word “stick” would have the same vector representation in both and all the other possible use cases.

Having a “deep” characteristics ELMo representations are a function of all layers of the deep pre-trained biLM. They are a linear combination of the vectors stacked above each input word for each end task. This method allows higher LSTM levels to capture context-dependent features of word meaning and lower LSTM levels to seize the syntax, and overall leading to better model performance. The purely character-based representations of ELMo allow the network to capture the inner-structure of the word and use morphological information for the words which were not observed during training. Furthermore, the neural network is capable of distinguishing between the words coming from the same root such as beauty and beautiful, while it discerns these words are related.

Let’s set up our system for ELMo!

# We use TensorFlow Hub with Keras for ELMo representations

import tensorflow_hub as hub

import tensorflow as tfAn example of how ELMo embeddings looks like:

- The first dimension represents the number of training samples.

- The second dimension represents the maximum length of the longest string in the input list of strings. As we have only 1 string in our example, the longest input length is equal to 10.

- The third dimension is equal to the length of the ELMo vector. Thus, every word in the input sentence has an ELMo vector of size 1024.

3.3.1.2. Model Architecture

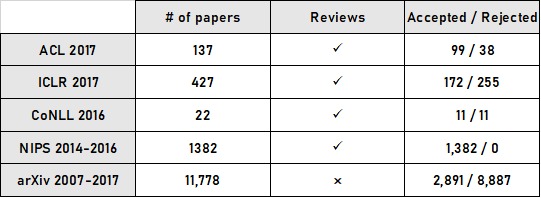

Figure 3: The Architecture of ELMo

Figure 3: The Architecture of ELMo

In ELMo model architecture, ELMo word vectors are computed on top of a two-layer biLM and they derive from the combination of intermediate word vectors as illustrated in the figure.

- Step 1: The model consists of two bidirectional LSTM layers that allow the model to contain information not only from the words on the left-hand side but also from the ones on the right-hand side.

- Step 2: The raw word vectors are the input of the first biLM layer through the backward and forward pass.

- Step 3: Word vectors exiting the first LSTM layers constitute the first intermediate word vectors.

- Step 4: They pass through the second biLM creating the second intermediate word vectors.

- Step 5: The final ELMo representation is the weighted sum of the raw word vectors and the two intermediate word vectors.

Let’s have a look at how we implement this process in Python!

We firstly call ELMo embeddings through TensorFlow Hub and define them.

embed = hub.Module("https://tfhub.dev/google/elmo/2")

def ELMoEmbedding(x):

return embed(tf.reshape(tf.cast(x, tf.string), [-1]), signature="default", as_dict=True)['default']As a second step, we define recall, precision and F1 score to add as our metrics. Due to our imbalanced dataset, we prefer to use F-Score as our model comparison metrics rather than accuracy since accuracy might be misleading when used in imbalanced datasets.

def recall_m(y_true, y_pred):

true_positives = K.sum(K.round(K.clip(y_true * y_pred, 0, 1)))

possible_positives = K.sum(K.round(K.clip(y_true, 0, 1)))

recall = true_positives / (possible_positives + K.epsilon())

return recall

def precision_m(y_true, y_pred):

true_positives = K.sum(K.round(K.clip(y_true * y_pred, 0, 1)))

predicted_positives = K.sum(K.round(K.clip(y_pred, 0, 1)))

precision = true_positives / (predicted_positives + K.epsilon())

return precision

def f1_m(y_true, y_pred):

precision = precision_m(y_true, y_pred)

recall = recall_m(y_true, y_pred)

return 2*((precision*recall)/(precision+recall+K.epsilon()))Then, we build our NLP model using ELMo vectors for our text classification task where we try to predict the manuscript’s classification as accepted or rejected based on its reviews.

The model takes untokenized sentences as input and tokenizes each string by splitting on spaces. Moreover, the input is a string tensor with a shape of 1, which indicates the batch size. [18]

Finally, we train our model on the dataset in 10 epochs with a batch size of 16 and validate on our test dataset.

3.4. Universal Language Model Fine Tuning (ULMFit)

ULMFit proposes an effective transfer learning method which can be applied to any type of NLP task, that puts forward key techniques that are crucial for fine-tuning [8]. Before the introduction of ULMFit, existing transfer learning methods for NLP required task-specific modifications or training from scratch. As also mentioned in section 3.2, in real word NLP tasks, it is often observed that our existing domain and the domain of interest might differ greatly. To solve this problem, Ruder and Howard combined the fine-tuning technique with traditional transfer learning methods to improve the transfer learning process. With ULMFit architecture, we can now achieve higher accuracy and better performances with fewer data and time as the model does not need to learn everything from scratch [7].

ULMFit introduces new approaches to better tackle solutions such as finding documents relevant to the legal case, identifying spam, bots, and offensive comments; classifying positive and negative reviews of products and grouping articles by political orientation [7].

3.4.1 Methodology

The model structure consists of the AWD-LSTM language model, an LSTM (without attention, short-cut connections, or other additions) along numerous tuned dropout hyperparameters[8]. As its name suggests, ULMFit is designed to be universally applicable approach in that it has the following features: it works across tasks varying in document size, number, and label type; uses a single architecture and training process; requires no custom feature engineering or preprocessing and does not require additional in-domain documents or labels [7]

The necessary packages to construct an ULMFit model can be downloaded as shown below. Besides, if one wants to study further the building blocks of the ULMFit model can benefit from Jeremy Howard’s lectures from here.

#pip install torch_nightly -f https://download.pytorch.org/whl/nightly/cu92/torch_nightly.html

import fastai

from fastai import *

from fastai.text import *

from functools import partial

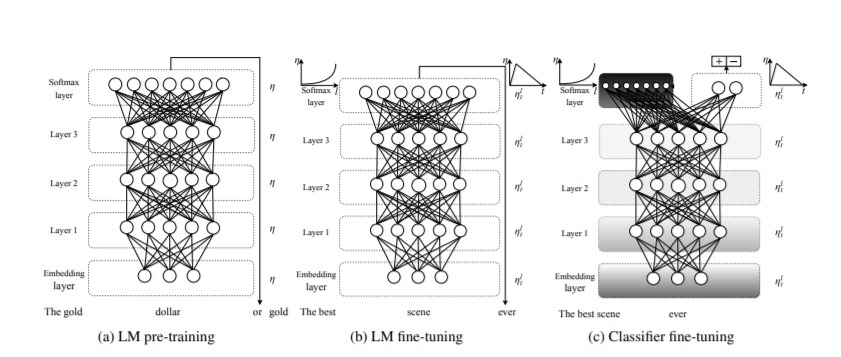

import io Figure 4: The Architecture of ULMFit [8]

Figure 4: The Architecture of ULMFit [8]

The figure above shows the steps of the ULMFit model: a) General-domain LM pretraining; b) target task LM fine-tuning; and finally c) target task classifier fine-tuning [8]. In the following sections, we will briefly explain each step and its key features.

3.4.1.1. General Knowledge Domain Training

To start with, one needs to create a language model to gather information for transfer learning. A language model is an NLP model that is trained to learn predicting the next word in a sentence. To do so, it is important to acquire a reasonably general and large language corpus to train a universal language model that is suitable for fine-tuning [7].

ULMFit model uses Stephen Merity’s Wikitext 103 dataset which is created from a pre-processed large subset of English Wikipedia consisting of 28,595 preprocessed Wikipedia articles and 103 million words [7] [8]. The original dataset is available here.

Training the language model has been done by running the text corpus through a bidirectional language model with an embedding size of 400, 3 layers and 1150 hidden activations per layer [8]. In our analysis, we download the pre-trained model through the ‘fastai’ package and there is no additional required code to preprocess the text as it is a built-in in the package’s function. The code for pretraining the language model is available online, however it takes approximately around 2 to 3 days by a computer with a decent GPU. Since we aim to benefit from transfer learning, we will not be training a language model.

3.4.1.2. Target Task Language Model Fine Tuning

After acquiring the language model, we will now elaborate on how to transfer learning works on our actual data. Using only a single layer of weights (embeddings) for transfer learning has been convenient for some years thanks to their ease of use, however, these weights only penetrate through the surface of the neural network. However, in practice, neural networks usually contain more than one layer, so the information has to be transferred to other layers otherwise information from transfer learning might be lost in the process.

Ruder and Howard make use of Average SGD Weight Dropped LSTM, AWD-LSTM in short, which is introduced by Stephen Merity for language modeling to prevent information loss during transfer learning. The weight-dropped LSTM benefits from DropConnect instead of a de facto dropout, which drove a dramatic improvement over past methods for language modeling [9].

Dropout sets randomly selected subset of activations to zero within each layer while DropConnect sets a randomly selected subset of weights within the network to zero [11]. Dropout, so far, was successful, however, it is found to be somewhat ineffective for transfer learning as it disrupts the Recurrent Neural Network’s ability to retain long-term dependencies. Besides AWD-LSTM, fine-tuning is another key characteristic of the ULMFit model. Since our data has a different distribution than Wiki Text103, we have to fine-tune our language model along with the PeerRead data. However, if the fine-tuning has been done aggressively or ineffectively, it is usually observed that the model suffers from catastrophic forgetting. Because of that, they propose three new methods that are crucial for retaining previous knowledge and prevent catastrophic forgetting [8]: 1) discriminative fine-tuning: 2) slanted triangular learning rates; 3) gradual unfreezing. These three processes enable the model to train a robust language model even for small datasets. Gradual Unfreezing: This method suggests that instead of fine-tuning all layers at once, we gradually unfreeze the model starting from the last layer where it contains the least general information to the first layer where the most information is hidden [13]. In application, we first unfreeze the last layer and train it for one epoch, then we unfreeze the next layer and train for another epoch and continue these steps until we unfreeze all the layers in the model. This approach is implemented in our code with ‘freeze_to’ function as in freeze_to(-1) would indicate that we are freezing all LSTM layers except the last layer.

Discriminative Fine-Tuning: Also indicated in gradual unfreezing, each layer in our model has to be trained separately to obtain the highest possible information as each layer contains different types of information. Hence, so it is worth to fine-tune them to different extents. In discriminative fine-tuning, instead of using the same learning rate for all layers, we assign different learning rates to each layer [8][13]. During the empirical studies in this field, it was discovered that first fine-tuning the last layer, and then unfreezing all the layers step by step until all the layers are unfrozen works well with lowering the learning rate by a factor of 2.6 on each step [8].

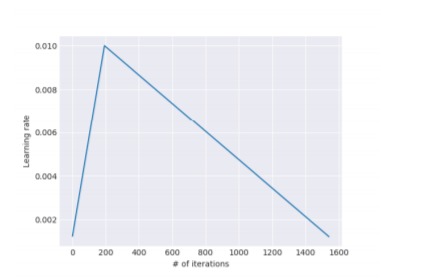

Slanted triangular learning rates: When we are assigning different learning rates for each layer, we need to find the optimal learning rate that would fit the training efficiently. Rather than manually setting the learning rate for each layer, Howard and Ruder deploy the slanted triangular learning rate method to the model to converge to a suitable region of the parameter space at the beginning of training and then refine its parameters [8]. The idea of slanted triangular learning rate is that it first linearly increases the learning rate and then linearly decays it meanwhile trying to find optimal learning late [12]. In ULMFit implementation, ‘fit_one_cycle’ function and ‘lr_find’ help us employ this method.

Figure 5: Slanted Triangular Learning Rate Schedule

Figure 5: Slanted Triangular Learning Rate Schedule

Here, we can observe the possible good learning rates for our training, however, it is suggested to use fit_one_cycle with a learning rate slightly bigger than the plot shows as we will perform slanted triangular learning rate schedule in fit_one_cycle function. In our case, the value of 1e-2 seems good to start with. When using the 1-cycle learning rate policy, we determine 2 values for momentum, first one for higher bound and the other one for the lower bound. The implementation of the momentum is two ways: first, we decrease the momentum from higher to lower bound and then we do the opposite. Based on Ruder and Howard’s paper, this cyclic momentum gives a similar result to set the parameter manually, however it is crucially useful in terms of time-saving [8][12].

The accuracy implies how good the language model is at predicting the next word in the sentence. As a reminder, we are still training our model to learn how to predict the next word in a sentence. We finally save our fine-tuned language model trained with our target and domain data.

3.4.1.3. Target Task Classifier

Fine-tuning the target task classifier is the most critical part because now we will finally be able to use all gathered information the deploy on our task. Similar to how to fine-tune the language model, we also need to fine-tune the target task classifier as overly aggressive fine-tuning will cause catastrophic forgetting and being too cautious would result in a slow convergence and thus overfitting [8]. Therefore, we apply three key approaches in fine-tuning as well on target task classifier training: gradual unfreezing, discriminative fine-tuning and slanted triangular learning rates.

First, we need to upload the target data once again, this time for creating the text classifier. With ‘text_classifier_learner’ function, we can specify our actual task. Then we will start fine-tuning according to our target task.

When using fit_one_cycle, one can benefit from ‘slice’ function. The first element of slice indicates the start and the last shows the end, and the remaining are evenly geometrically space. As you go from layer to layer, we decrease the learning rate. The lowest levels are given smaller learning rates so as not to disturb the weights much. In order to make predictions, we add our test data to the model and use ‘get_preds’ function from the package.

3.5. Support Vector Machine (SVM)

The support vector machine is a supervised machine learning algorithm that relies on the idea that input vectors are non-linearly mapped in very high-dimension feature space [14]. SVM algorithm fits these input vectors according to their labels, and through the characteristics of the data points, it determines where the new observation belongs in the model labeling. Let’s imagine a big set of two-dimensional training examples, similar to a scatter plot, each point belongs to one group or the other of two categories. SVM algorithm runs a non-probabilistic binary linear classifier that assigns new data points to either of the categories. Since we are running a binary classification, we can use the SVM algorithm directly. However, it is also possible to make an analysis with multi-class labeled data or with unlabeled data, unsupervised learning, but the algorithm has to be adjusted [15].

The recipe for applying Support Vector Machine for NLP tasks is quite easy to implement.

- First, we start by downloading the necessary packages.

- We split our data into test and train. Our variable of interest is the author’s affiliation with an institution.

- Later, we encode the labels of the target variable, in our case its acceptance of the paper.

- We vectorize the words by using a vectorizer function. In our model, we decided to apply TF-IDF because it is good to find how important a word in a document is in comparison to the corpus. We only fit on our train data, since it is usually bigger and we need to create a matrix as broad as possible. Afterward, we transform both train and test to create a sparse matrix that both transformed matrices are as wide as the train sparse matrix.

- Finally, we run the algorithm to make the classification and check the good of fitness.

4. Empirical Results & Conclusion

4.1. Results

We used ELMo and ULMFit for our review-based text and content-based (abstract) classification analyses to predict whether a paper is accepted or rejected, and compared the results with a benchmark of Lasso Regression. As comparison metrics, we checked both for accuracy and F-score, where the latter is likely to present more reliable results due to our imbalanced dataset.

In all three models we worked with, we obtained better results - higher accuracy and F-score - in the review-based analysis. This is a relieving finding for us reflecting that reviews are indeed not meaningless or inconsistent with each other to a large extent. They still do have a high predictive power - and definitely higher compared to abstracts that contain contextual informative words in short paragraphs. The ELMo model has the highest accuracy among three with 78.55%, whereas Lasso Regression has a slightly higher F-score than ELMo with 87.89% compared to 87.68%. ULMFit has, on the other hand, the lowest accuracy and F-score. These scores were reached after tuning the model for our dataset. Yet in ELMo case, for instance, we only used 10 epochs due to computational heaviness. With a larger number of epochs and a more powerful computational system, the scores could be different.

In the content-based analysis, we have the same pattern in which the highest accuracy belongs to ELMo with 77.71% and the highest F-score belongs to Lasso Regression with 58%. We can easily observe the huge drop in the F-score demonstrating the low predictive capability of abstracts. ULMFit, nonetheless, obtained significantly lower scores both for accuracy (70.5%) and F-score (35.5%).

In the dataset of review-based analysis, we face an imbalance of 74% acceptance and 26% rejection whereas for the dataset abstract-based analysis the proportions are vice versa with 33% acceptance and 67% rejection. Although the datasets are not entirely balanced, one can still argue that an imbalance of 1:3 or 1:2 may be acceptable. Nevertheless, we examined the case for our dataset and ran our entire analysis again with balanced undersampled data. However, the results we obtained were significantly lower. Besides, in the text classification dataset, we did not prefer oversampling by creating new texts for reviews and abstracts due to the problem of reliability. Therefore, we only considered and compared the results with the entire dataset without undersampling.

Lastly, we used SVM for our analysis with auxiliary data in which we elaborated on the author’s institution. We predicted papers’ acceptance based on only the authors’ affiliations, only review, and both affiliation and review to be able to discern affiliation’s impact in comparable settings. Our first finding is SVM’s lower performance compared to the other two models and the benchmark we used. SVM could only reach an accuracy of 72.86% and an F-score of 82.57% with a single input of reviews. Surprisingly authors’ affiliation has certainly lower predictive power on article classification and had an accuracy of 65.71% and an F-score of 78.57%. When we based our predictions both on review and affiliation, we obtained almost the same results as the only affiliation - this time only with a hardly higher F-score.

4.2. Discussion and Conclusion

In this blog post, we studied the first public dataset of scientific peer reviews available for research purposes PeerRead applying state-of-the-art NLP models ELMo and ULMFit to a text classification task [1]. We examined the importance of the peer reviews on paper’s acceptance or rejection decision in well-known conferences of computational linguistics, AI and NLP by using paper’s abstract, reviews and author’s affiliation. We detected that abstracts and authors’ affiliations do not have substantial predictive power. The results have shown that one could determine by nearly 80% accuracy whether a paper will be accepted or not by analyzing its reviews with deep learning methods. While the reviews appear to be successful at predicting - or leading to - paper’s classification based on our pre-labeled dataset, it is still a question if reviews are truly objective and consistent since the reviews themselves might create an inconsistency considering the NIPS Experiment (2014).

5. Reference List

[1] Kang, D., Ammar, W., Dalvi, B., van Zuylen, M., Kohlmeier, S., Hovy, E., & Schwartz, R. (2018). A dataset of peer reviews (peerread): Collection, insights and nlp applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.09635.

[2] Google Scholar. (n.d.). In Wikipedia. Retrieved January 27, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Google_Scholar

[3] Scholarly 0.2.5. Retrieved Jan 27, 2020, from https://pypi.org/project/scholarly/

[4] Tang, J., Li, H., Cao, Y., & Tang, Z. (2005, August). Email data cleaning. In Proceedings of the eleventh ACM SIGKDD international conference on Knowledge discovery in data mining (pp. 489-498).

[5] Sebastian Ruder, NLPs ImageNet moment has arrived, The Gradient, Jan. 27, 2020, https://thegradient.pub/nlp-imagenet/

[6] Pan, S. J., & Yang, Q. (2009). A survey on transfer learning. IEEE Transactions on knowledge and data engineering, 22(10), 1345-1359.

[7] Jeremy Howard & Sebastian Ruder , Introducing state of the art text classification with universal language models, Retrieved Jan 29, 2020, from https://nlp.fast.ai/classification/2018/05/15/introducing-ulmfit.html

[8] Howard, J., & Ruder, S. (2018). Universal language model fine-tuning for text classification. arXiv preprint arXiv:1801.06146.

[9] Merity, S., Keskar, N. S., & Socher, R. (2017). Regularizing and optimizing LSTM language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:1708.02182.

[10] Langford J. and Guzdial M. (2015) The arbitrariness of reviews, and advice for school administrators. Communications of the ACM Blog 58(4):12 13.

[11] Wan, L., Zeiler, M., Zhang, S., Le Cun, Y., & Fergus, R. (2013, February). Regularization of neural networks using dropconnect. In International conference on machine learning (pp. 1058-1066).

[12] Smith, L. N. (2017, March). Cyclical learning rates for training neural networks. In 2017 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV) (pp. 464-472). IEEE.

[13] Yosinski, J., Clune, J., Bengio, Y., & Lipson, H. (2014). How transferable are features in deep neural networks?. In Advances in neural information processing systems (pp. 3320-3328).

[14] Cortes, C., & Vapnik, V. (1995). Support-vector networks. Machine learning, 20(3), 273-297.

[15] Support-vector machine (n.d.). In Wikipedia. Retrieved January 31, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Support-vector_machine#Multiclass_SVM

[16] Peters, M. E., Neumann, M., Iyyer, M., Gardner, M., Clark, C., Lee, K., & Zettlemoyer, L. (2018). Deep contextualized word representations. arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.05365.

[17] What is peer review? Retrieved on Feb 01, 2020, from https://www.elsevier.com/reviewers/what-is-peer-review

[18] AI HUB, Retrieved on Feb 05, 2020, from https://aihub.cloud.google.com/p/products%2Fd73ce2af-1179-4af9-bd2d-ffae7ea9f9ff